Overview

The lines between our identities and digital personas are blurring. We use more digital services than ever before, and like the unfiltered exhaust pipes of vehicles, belch out a noticeable trail which follows us. The digital services we use are extensively data driven. As the digital age advances, our reliance on technology is exponentially increasing. Devices like Alexa listen to what we speak, our locations are used for services like Uber and Lyft, and we leave more digital footprints than ever before. This age requires a new definition of privacy where data driven services and analytics can co-exist with privacy - Differential Privacy is the answer.

Some History

Differential Privacy is not trying to solve something novel here- privacy preserving data analysis is a 50+ year old problem. Every service, or software that is data driven must tackle this. One example is the census which needs data for the well being of people but needs to preserve privacy. In a way, it is a marriage of 2 diametrically opposite outcomes- Privacy of the user and data-analytics from user data.

One of the earlier suggested solutions to this was “De-anonymization”. De-anonymization attempts to preserve user privacy by removing the sensitive information from the data-set before having allowed access for data-analysis. This may be done by removing it or randomizing columns. This looks to be a good solution at first glance, but as you would see there is a fundamental problem.

Let’s go back to 2006, the Netflix Prize was announced, they were looking for collaborative algorithms to predict user ratings for films. I know what you guys are thinking- Netflix existed in 2006??!!. Yes, it did, it was founded in 1997, and it started out as an online DVD rental service. To protect user’s privacy the algorithm had access only to previous ratings and the uses were only being identified by the numbers assigned for the contest. Pretty solid privacy protection? Two researchers at University of Texas, Austin compromised this and performed a linkage attack, and published the results in a paper “Robust De-anonymization of Large Sparse Datasets”. To put it simply they analyzed data-sets of movie ratings which had user information from sources like IMDB, and with good accuracy were able to corelate matches and de-anonymize the netflix data set. They could do it from other data sources, but their approach was novel. I strongly suggest reading the paper to those interested in privacy. This served as an important lesson - Linkage attacks could possibly de-anonymize your data even if it is preserves privacy isolated, and this could happen years after as well, if there is some data-set that could be used to achieve this.

By no means, this was a one-off case. A similar linkage attack was performed on NYC taxi data.

- “https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jun/27/new-york-taxi-details-anonymised-data-researchers-warn” .

- https://www.fastcompany.com/3036573/nyc-taxi-data-blunder-reveals-which-celebs-dont-tip-and-who-frequents-strip-clubs

We realized that overly accurate statistics can blatantly compromise privacy. Once this was established, an alternative solution was needed. Differential Privacy was developed by cryptographers, and hence a lot of the mathematical definitions and terminology stems from there.

In 2006, Cynthia Dwork, Frank McSherry, Kobbi Nissim and Adam D formulated a ground-breaking mathematical definition of Differential Privacy, and quantified the privacy loss incurred as ‘ε’, and also a general purpose mechanism of achieving it. A lot of what I learnt, and the source material for this blog is inspired by her talk on differential privacy

The Approach of Differential Privacy

So to begin, we must outline our problem well, and ask some fundamental questions. Firstly, it is important to state our goal “Learn trends in datasets without compromising the privacy of the individual”.

Some of the questions we should be asking are:-

- Could we learn same things if an individual is removed from the data set?

- But can learning about population as a whole hurt an individual’s privacy? Maybe it can, but this should be irrespective of the fact whether the individual is present in the dataset or not.

With this the english language definition of privacy is as follows : “The outcome of analysis is equally probable whether any individual joins the dataset or refrains from joining it”.

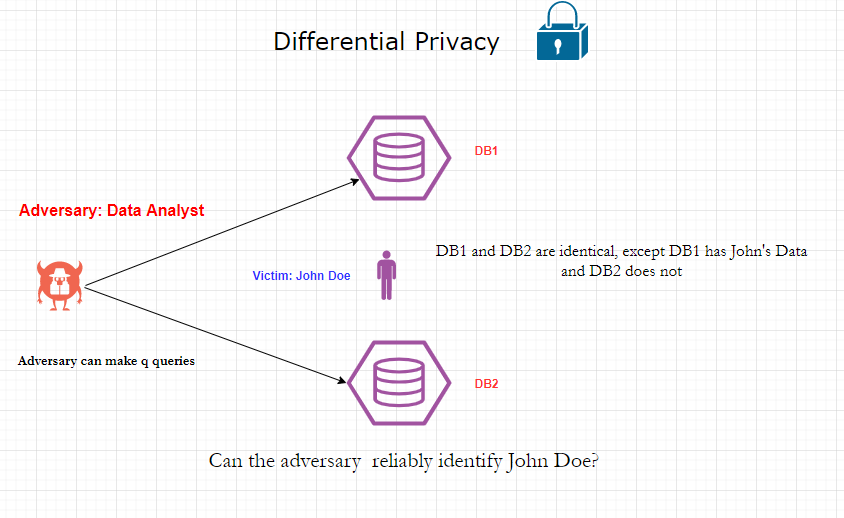

The idea behind Cynthia Dwork and her fellow researcher’s work was that a person’s privacy cannot be compromised from the database if the person was absent from the database. So if the database were to behave indifferently to the analytic queries,whether the said person was present or not, this would preserve privacy. To formulate, it we can think of the person querying the database for analytics as the adversary. The oracle in cryptography terms is the database, and the individual is the target (Alice/Bob).

|

|---|

| Indistinguishability in both scenarios to preserve privacy |

Let this algorithm which ensures the differential privacy above be A, then we can state that: Algorithm A gives (ε) differential privacy if for all pairs of data sets x,y differing in the data of 1 entity/person and all events S. This means that dataset x has the individual’s data, and y does not. If for all pairs x,y (all such combinations where the dataset of one person is removed):-

Pr[A(x)∈S] = eε . Pr[A(y) ∈ S]

S, here is the set of all possible outcomes of the queries forwarded by adversary to the Oracle. So it could be a SELECT query with a where clause or whatever, and the outcome of the queries are dataset y. or the data storage and the above equation says that the Algorithm A run on the dataset x to return the Outcome ‘s’ and the same algorithm run on dataset y to return the outcome for ‘s’ would differ by a very small quantity eε. If eεis small, then Algorithm A succeeds in this context for differential privacy. The mathematical definition would be known as eε-differentially private algorithm.

The paper by Cynthia Dwork and team, on Differential Privacy:-Algorithmic foundations of Differential Privacy.

Implementing Differential Privacy

To get started, one must understand that this is not a simple problem to solve whatsoever. In theory, even if we were to come up with a solution , there would be many caveats and challenges to implementing it widescale- Eg: If this requires a completely new system, and does not integrate with existing ones, it will not be adopted. Most organizations cannot feasibly scratch their entire analytics based architecture in favour for a new one. Additionally, it must be flexible across data platforms, if the solution only works on a few data architectures, it would not be of much use either.

A lot of companies are yet to adopt differential privacy, as it is still a hard problem to solve feasibly. For eg:, The randomness and noise approach require that we work with very large data sets or else it would not be feasible. The major roadblock here is of converting the theoretical work into general purpose implemenations.

What would constitute a real-world implementation of differential privacy?

- Have broad support for analytic queries: Trend analysis and data analysis have a wide range of queries, differential privacy solutions should not compromise functionalities as it would then make them difficult to adopt.

- Usability for non-experts: Implementing it into different software services and data environments should be easy, and the developers doing this should be able to do this without being privacy or differential privacy experts.

- Easy integration with existing architecture and data environments: The solutions should be easy to integrate with existing data environments without having to build entirely new systems and services from scratch.

Differential Privacy mechanisms

Differential privacy mathematically becomes a probabilistic concept,and so does any differential privacy mechanism. For implementation, they used an algorithm with plausible deniability. This means that the algorithm would randomly flip data bits to cause the output to be changed. This would be like adding randomness to the query output, and hence the individual’s data returned by that query cannot be trusted due to plausible deniability. On the other hand, the randomness added to the large data set would not matter in the overall data or trend analysis.

There are some other mechanisms as well like Laplace Distribution which adds extra output to the queries in forms of Laplace noise to name a few.Some other different mechanisms for differential privacy.

- PINQ

- Elastic sensitivity

- Sample and Aggregate

- Restricted sensitivity

Uber has been doing some excellent work in privacy engineering. In 2018, in an USENIX talk they introduced the “CHORUS” framework. It was a novel framework as it touched base upon all the points covered in real-world implementation requirements and more.

The following is from my notes of their USENIX talk on What makes Chorus so good?

- Rewrites SQL queries, while earlier approaches modify the database mechanisms, chorus does not require any such changes to the database engine or data. This satisfies easy integration with existing data environments.

- What it does is modifies the SQL queries in place to convert them to intrinsically private queries. It is a query rewriting system.

- Query has embedded diff privacy, it can be run on any database, and these would generate differentially private results and this would be returned to the analyst.

One of the underlying mechanism used by Chorus, is “Elastic Sensitivity” developed at UC Berkley. This adds Laplace noise to the query, however with a twist. The amount of noise adde depends on the queries’ sensitivity, and scaled to that. The sensitivity of the query is determined by the “Elastic sensitivity” which computes an efficient upper bound on the quergdask das dsa

Example Mechanism: Elastic Sensitivity (Developed at UC berkley)

Sensitive query result. Add noise. differentially privacy result. noise is drawn from the laplace distribution. Amount of noise depends and scaled to queries’ sensitivity. Now the next question is how do we decide the sensitivity of a query? This is determined by the approach termed elastic sensitivity. Some queries are more sensitive to information of individual. The exciting part is it supports query joins as well.

To grossly oversimplify this, Chorus uses it to rewrite the queries using this elastic sensitivity as a parameter before sending it off to the existing database, acting as a middle man between the analyst and the data-store. This also ensures that the compatibility is maintained across different data environments.

Conclusion

Differential privacy is here to stay and multiple companies such as Google, Apple , Microsoft and Uber are trying to integrate this into their data-environments. Thanks for reading to the end of the blog. I might write a blog on the Chorus framework, once I have a better understanding of it and delve into the implementation details, for now I have just explained it from a high level functional perspective.